In this double interview we finally talk about Italy with two Professors, Filippo Tronconi and Gianfranco Baldini, who are investigating Giorgia Meloni’s Brothers of Italy. This is an important interview that makes up, at least in part, for POP’s lack of attention to Italy. Being an Italian myself, I have always preferred not to deal with Italy because Italian politics (as interesting as it is) is also neurotic, unbearable, and at times incommentable.

The time to open this wound and look into it has finally come.

Tronconi and Baldini explain the electoral success of Brothers of Italy, a relatively new party that replaced Salvini’s Lega as the biggest party in the conservative camp. They help us understanding many important aspects of Brothers of Italy. First, what kind of party is it? Populist radical right? Nationalist and conservative? Neofascist? Second, how is it possible that the first female Prime Minister in Italy is not at all interested in any feminist agenda but rather proposes a traditional family model? And how did the party change once it won the elections and took power? Is Giorgia Meloni going to try and Orbanize Italy? How could she go from admiring Putin for years to endorse the sending of weapons to Ukraine?

The answers to these and many other questions in this long, dense interview.

Enjoy the reading…

1) Before we begin, could you please tell us why you decided to study populism? Is there any particular study or author that sparked your interest?

FT) If you live in Italy and are interested in politics, it is hard to avoid asking yourself questions about populism. I started my BA studies at the Faculty of Political Science in Florence when Silvio Berlusconi was announcing the establishment of Forza Italia and Umberto Bossi’s Northern League was achieving its first successes. A few years later the anti-corruption judge Antonio Di Pietro formed his own party, then came Beppe Grillo, Matteo Salvini, Giorgia Meloni. Marco Tarchi aptly referred to Italy as “The promised land of populism.” He was not wrong.

From a more academic standpoint, while studying ethno-regionalist parties for my PhD, I frequently pondered the nature of the Northern League and the mix of autonomism, nativism, and populism within its political agenda. Reading Par le peouple, pour le peouple, by Yves Mény and Yves Surel was very important at that time (I actually read the Italian translation published by Il Mulino). Their reflections on the democratic tension between populism and constitutionalism, as well as their idea of keeping analytically distinct three different conceptions of the people (people-as-sovereign, people-as-class, people-as-nation) seemed enlightening to me and continue to hold relevance today. This is particularly noteworthy considering that their book was published prior to the surge in popularity of populist studies—before the publication of Cas Mudde’s article The Populist Zeitgeist in 2004 and before the populist Zeitgeist itself. In my opinion, that book has received far less circulation and appreciation than it truly deserves.

GB) Filippo and I have now worked together on populism and the ‘Brothers of Italy’ for more than one year, and yet we never got to discuss how we first came to approach populism as a research topic. It is interesting that if I now have to identify the most influential work, I would also pick Meny and Surel’s book, that I read in March 2002, on a long train journey back from Paris to Bologna, at the end of my post-doctoral fellowship at the Cevipof. To be sure, my interest on the topic came, about a decade before this, from my attendance of Piero Ignazi’s classes (and his supervision of my first works) as well as from the possibility of witnessing directly the weight of populism in the political transition that Italy was experiencing when I obtained my BA degree, just two days before the first Silvio Berlusconi’s electoral breakthrough, in March 1994. In this respect, my first field research was at the Fiuggi Conference in 1995, when the neo-fascist MSI turned into National Alliance – a thoroughly fascinating experience for a young graduate student! This led to my first publication on the topic for the Istituto Cattaneo’s journal ‘Polis’. This happened in the same period when, as a Master student at the LSE, I went on to study Umberto Bossi’s Northern League, by reading also some of the classics, such as Ionescu and Gellner’s book.

In reading Meny and Surel, I became interested in studying the rising stars of European populism (not just Berlusconi and Bossi in my country, but also Haider in Austria and many others), by placing their experiences in a broader context, particularly in the region where populism had long been dominant, namely Latin America. At that time, as the editorial assistant of ‘Polis‘, in Spring 2002, my initial idea was to ask my future colleague Loris Zanatta – a renowned expert of Latin America – to write a review article on populism for the journal. This piece, which also analyzed other authors I had read by then (such as Betz, Canovan, Eatwell, Hermet, Taggart), further fueled my interest in understanding populism from a comparative perspective.

2) Let’s now move the the topic of an article you recently published together: Brothers of Italy. Fratelli d’Italia (FdI) was a party that struggled to obtain significant electoral results, with performances below 5% of the votes both in 2013 and 2018. How do you explain the fact that in 2022 they jumped to 26% of the votes and now lead a government coalition together with Berlusconi’s Forza Italia and Salvini’s League?

First, the traditional issues of the Italian right have been achieving success for decades now. That is why the overall success of the FdI-FI-Lega coalition in 2022 is neither surprising nor exceptional. The 43% of the votes the coalition got is not far from similar percentages obtained in the 1990s by centre-right coalitions, or in the elections of 2001, 2006, 2008. In Italy, the conservative camp has consistently enjoyed greater support than the progressive camp, and whenever the latter has emerged victorious in general elections, it is primarily due to divisions among right-wing parties.

The interesting aspect is therefore the success of FdI within the right-wing coalition. In our view, this can be explained not so much by a particularly innovative FdI’s political proposal. While Forza Italia is now a declining party (its decline began well before Berlusconi’s passing), the positions of FdI and Lega align closely on most relevant issues. These include a hostile stance towards immigration, defense of traditional values, advocacy for the economic interests of the numerous small business owners in Italy, safeguarding the traditional family against an alleged “gender theory” that seeks to blur or erase gender distinctions, and skepticism or outright hostility towards the European integration project. What has made a difference in 2022, then, is Giorgia Meloni’s personality, as opposed to Matteo Salvini’s declining leadership, and the credibility and consistency of the party. Throughout its existence (since its foundation in December 2012), FdI has refrained from participating in any coalitions. In contrast, Lega has engaged in various types of coalitions, even including ones considered “awkward” or unconventional, such as the “yellow-green” government (Five Star Movement-Lega, 2018-19) or the technocratic government led by Mario Draghi (2021-22). Once again, right-wing Italian voters have demonstrated their unity and pragmatism. They consistently reward parties and individuals who exhibit credibility in assuming leadership within the coalition.

Finally, in addition to programmatic issues and the leader’s personality, we should perhaps underscore the organizational solidity of FdI. Despite being relatively young, having emerged just over a decade ago, FdI possesses deep roots in pre-existing organizations (and political culture), namely those of the Italian Social Movement (Movimento Sociale Italiano – MSI) and National Alliance (Alleanza Nazionale – AN). In an era where politics is predominantly dominated by communication, this aspect sometimes receives insufficient attention. However, the presence of a territorial structure, alongside the capacity to engage and mobilize potential voters at the grassroots level, remains crucial elements for electoral success.

3) Brothers of Italy has been classified by several experts as a populist radical right party (see here and here for example). Many point to the fact that the party has post-fascist roots, while often one can read that Brothers of Italy is in fact a national-conservative, populist, far-right or simply right-wing party. Let’s make some conceptual clarity. How do you define Brothers of Italy, and why?

Undoubtedly FdI has identity roots in neo-fascism, which in Italy was embodied by the MSI for so many decades. The party has often laid claim to that political camp, even in controversy with Gianfranco Fini, leader of Alleanza Nazionale, who had explicitly distanced the party from its fascist roots. FdI was established in 2012 to restore the connection with the MSI that had been severed by Alleanza Nazionale and subsequently dissolved through its merger into the People of Freedom party founded by Berlusconi in 2008. However, characterizing FdI as a neo-fascist party today, in our view, would be incorrect. This is because certain essential characteristics of neo-fascism, such as the acceptance of violence as a method of political competition, have fortunately been abandoned. Instead, the party’s public discourse and official documents place emphasis on themes that are typical of the European radical right, such as Islamophobia and a more general hostility towards immigration, which are seen as potentially diluting Italian national identity. Just a few weeks ago, a prominent member of FdI even made reference to the concept of “ethnic substitution,” thereby invoking a widespread conspiracy theory about the so-called Great Replacement, whether consciously or unconsciously. Another central theme is the defense of the traditional family and the party’s antagonism towards the LGBTQ+ community, referred to as the “LGBT lobby” by Meloni. Sovereignism is another significant aspect. Taken together, these factors lead us to consider FdI as a member of the European radical right party family.

A neon ‘fascio’ exposed in the birthplace of Benito Mussolini. It used to be inside the ‘Casa del fascio’ in Predappio, Italy.

At the same time, we sense, perhaps more than other colleagues, the fragility and transience of such labels. Moving closer to government, and then becoming its main actor, has caused the party to moderate some of its positions and abandon some issues. For example, Meloni has repeatedly said that she does not intend to revoke same-sex civil unions (although she remains opposed to same-sex marriages), a stance she vehemently criticized just a few years ago. Similarly, FdI does not seek to change the abortion law. More generally, we believe that defining a party’s ideological profile is also influenced by contingent circumstances: being in government or in opposition, having or not having competitors on the right, acting in one country or another (the Italian radical right has certain characteristics, the German one has others, the British one still others, etc.), as well as the system of alliances within European institutions. Today FdI has begun a process of moderation and normalization partly as a result of favourable opportunities in that direction. How far that process will go and whether it is irreversible or not, we are unable to say.

4) In what ways Brothers of Italy is similar to Fidesz in Hungary or Law & Justice in Poland? And, on the other hand, what separates it from these two parties? Will Meloni try to implement an Orbanization of Italy?

There are some troubling similarities, yet also important differences. Meloni shares the values of a traditionalist society based on the defense of the traditional family. Additionally, the parties seem have long shown some similarities in their Eurosceptic tones which, in the case of Law and Justice, have been fostered by working in the same group inside the European Parliament.

However, we would argue that the structure of political opportunities in which the party is governing now is quite different from the one that marks the experiences of both Fidesz and Law and Justice. Two points can be made here. First, despite the harsh rhetoric on gender and civil rights mentioned above, it is far from clear whether Meloni harbors an agenda for an illiberal turn similar to the one witnessed in these two countries over the last decade, which involved curtailing civil rights and undermining institutional checks-and-balances (see Pirro and Stanley 2022). Second, while it is certainly true that Italy has been both marked by the prolonged populist success and has faced challenges to its democratic quality, we can identify institutional and cultural factors that could constrain the possibility of an illiberal shift.

Four elements, in particular, warrant attention. First, although electorally predominant vis-à-vis its coalition partners, FdI does not govern alone. Though the League is more radical than FdI on some issues, Forza Italia anchors the coalition to the center (as recently seen on some EU-related issues). Second, as seen during the previous Five Star Movement-League government, President of the Republic Sergio Mattarella, whose mandate will expire after the end of the current parliamentary term, can be regarded a guardian against institutional challenges, perhaps the most prominent element of a number of strong veto points foreseen by the Italian Constitution. Thirdly, Italy’s distinct position and involvement within the European Union, as well as its geographical location, also influence the party’s stance on European affairs. Despite occasional disputes with France over immigration or Italy’s pending ratification of the MES (European Stability Mechanism), FdI does not seek to directly confront Brussels. For instance, the party has not pursued its electoral promise to challenge the supremacy of EU law over national legislation. Lastly, the illiberal turns observed in Poland and particularly Hungary were based on a set of popular beliefs that facilitated the exploitation of an “anti-imperialist” narrative against the EU (see Csehi and Zgut 2021). This narrative aligns with the pursuit of nationalistic paths toward “illiberal democracies.” While Italy may not possess the strongest liberal civil society, it is challenging to envision a crisis of liberalism comparable to the one experienced in numerous Eastern European countries (see Dawson and Hanley 2016).

Of course, we have no crystal ball, and eight months of government are insufficient to form a solid assessment. However, at the moment we don’t see any Orbanization happening. The extent to which Italian opposition parties will be able to highlight some contradictions and ambiguities between the discourse and the policies implemented by FdI also remains to be seen.

5) It seems that in the story of the Italian far right in general, and Meloni’s political trajectory in particular, references to pop culture are numerous. From the Hobbit camps organized by Brothers of Italy’s political predecessor (MSI), to the Atreju festival named after The Neverending Story’s main character, or the memefication of the leader’s most famous speech (check this out), it seems plausible to imagine that the success of Brothers of Italy is at least partially linked to its links to pop culture. Do you think Meloni would obtain the same results without this pop component?

This is of course difficult to say. As we mention in one of our contributions, in Italy the ‘popularization’ of politics has played a role long before the ascendance of Meloni’s star. In that piece, we also demonstrate that much of FdI’s current inner circle originates from the network that Meloni cultivated through the Atreju Summer festivals, which aligns with the MSI’s deeply rooted “social” and popular components, fostered by its prolonged opposition during the Italian First Republic.

While consolidating the party’s core, Meloni has effectively engaged with a broader audience, largely facilitated by her adept use of social media platforms. This has ultimately contributed to her image as the fresh face of Italian politics. Additionally, her distinction as the first female Prime Minister in Italy has undoubtedly played a role. Moreover, she has demonstrated an ability to navigate the challenges faced by female populist politicians. Indeed, such politicians must strike a delicate balance between assertiveness and motherhood, femininity and competence. While achieving this balance was relatively straightforward during her time in opposition, her first eight months in office have shown her capacity to maintain it. In this respect, however, one should not underestimate the fact that, in general, televisions have been rather friendly to her, as part of a turn in which FdI aims to re-balance at her favor the political affiliations of journalists of public-TV RAI (the latter being for many decades very politicized).

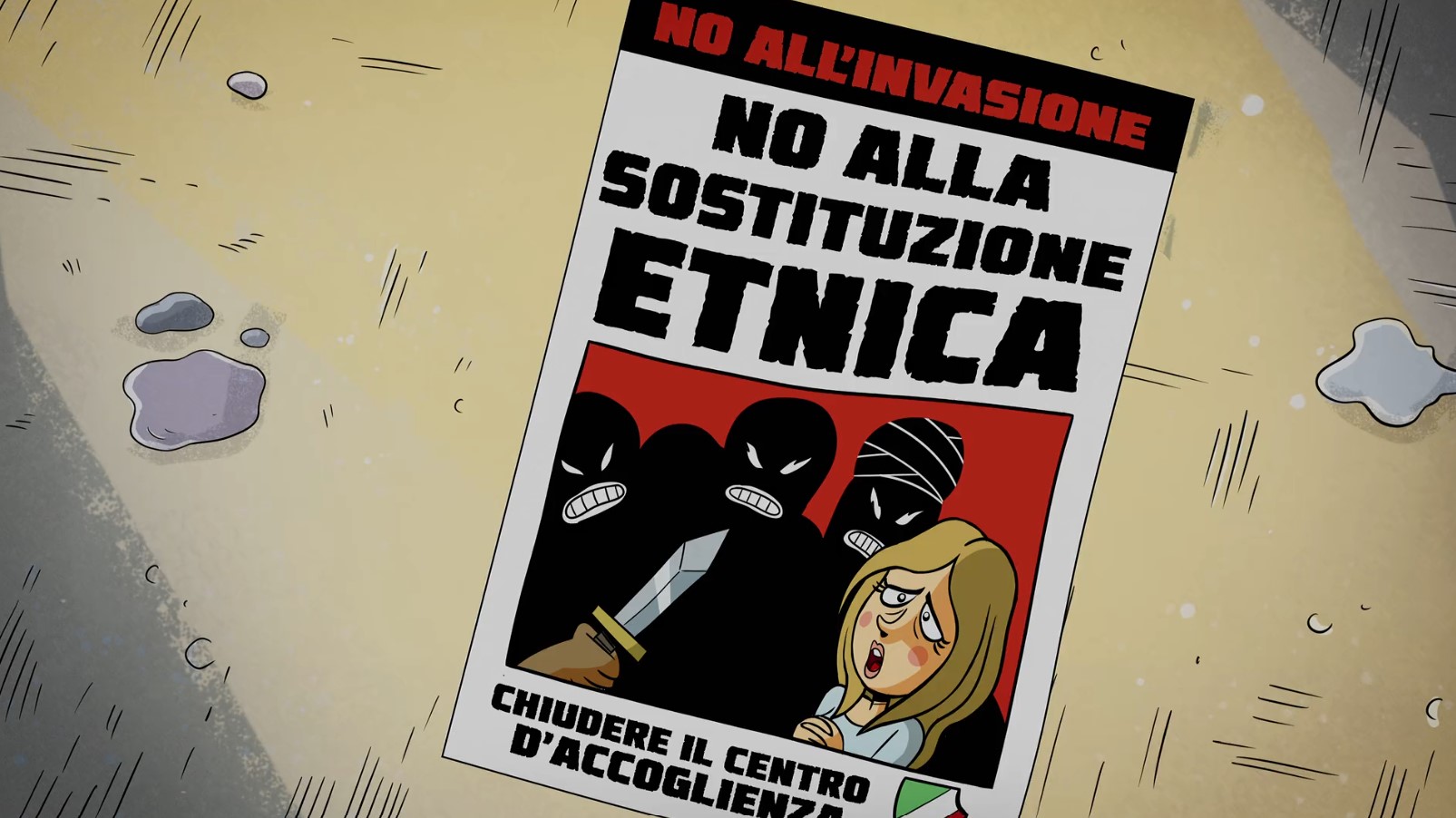

“No to invasion. No to ethnic replacement. Let’s close the migrants’ shelter.”

7) Another difficult balance concerns Russia: in the past Meloni has expressed pro-Putin and pro-Russia positions and we know that she is an admirer of Orbán. However, since the war she has been strongly in favour of shipping military equipment to Ukraine. Do you think that moving forward Brothers of Italy will adjust its position according to the situation, or will it remain clearly against Putin no matter what?

FdI has previously expressed admiration for Putin and displayed aversion to the sanctions imposed following the Crimea invasion. As recent as 2017, the party issued a congressional document known as the “Tesi di Trieste,” in which they stated, “we [FdI] do not share the logic of hostility toward the Russian Federation; instead, we believe that close economic and strategic cooperation between Europe and Russia is necessary and fruitful, particularly in combating terrorism.” Meloni’s autobiography, published in 2021, also demonstrates her admiration for Putin. However, this stance underwent a change in 2022.

In 2022, FdI swiftly and unequivocally condemned the Russian invasion and expressed support for sending arms to Ukraine, distinguishing itself from the League, which was not equally clear in taking a distance from Putin’s aggression. This shift aligns FdI more closely with Poland while creating a greater distance from Fidesz, which has maintained an ambiguous stance on the war in Ukraine. This change in attitude is indicative of the moderation process mentioned earlier and represents one of the clearest indications to date. As we suggested above, the structure of opportunities matters in parties’ attitudes and agendas. In 2022 FdI had the chance to approach the government and potentially hold the premiership. Aligning with NATO and the major European democracies meant sending a clear sign of reliability towards the electorate and the western allies. Additionally, FdI’s close link with the Polish governing party in the European Parliament may have played a role in shaping their stance.

8) A last observation about this contradictory party touches upon a topic you already mentioned earlier: while being opposed to same-sex marriage and in favour of restricting abortion rights, Brothers of Italy is one of the very few Italian parties with a female leader, and Meloni is the first female Prime Minister in Italian history. How do you explain this apparent paradox?

The Italian paradox is not an isolated case but rather a phenomenon observed across various countries. It is well known that a significant number of women have occupied or currently occupy leadership positions in radical right-wing parties, including figures such as Pia Kjærsgaard, Marine Le Pen, Frauke Petry, and Siv Jensen. In Italy, this paradox becomes even more pronounced due to the historical struggle of women in attaining important political offices. Meloni has played a crucial role in reshaping the image of her party, which was at risk of being perceived as residual and nostalgic. Her age provides a shield against accusations of continuity with fascism, while her status as a woman and a single mother signals the party’s capacity to represent social segments that are distant from the stereotypical right-wing imagery. However, the extent to which this image represents substance rather than mere symbolism is a separate question.

Recent research conducted by Elisabetta De Giorgi, Alice Cavalieri, and Francesca Feo, focusing on Meloni’s communication and FdI’s parliamentary activity, highlights that women’s issues receive limited attention in both institutional activities and digital communication. This indicates that descriptive representation, in terms of having women in leadership positions, does not necessarily correspond to substantive representation.

At this point, it may be more appropriate to reframe the issue. Increasingly, it is the left-wing parties that struggle with structural barriers in selecting female leaders. When considering the main European social-democratic parties over the past decade or two, how many female leaders can you recall? This inability to cultivate female leadership within left-wing parties might result in the paradox that the left might be unable to mobilize segments of the electorate that are particularly sensitive to feminist issues, while radical right parties attract more and more female voters.

The image used to illustrate the article is a frame of Zerocalcare’s TV show for Netflix, titled This World Can’t Tear Me Down. In the frame, Zerocalcare and his frend Secco are walking in their neighbourhood in Rome, where it is very visible the writing on the wall “Italy to Italians” and a Celtic cross very much in vogue in neo-fascist circles. The image about ‘ethnic substitution’ is from the same TV show.

Gianfranco Baldini is an Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of Bologna and a Research Associate at the University of Surrey. His most recent publications include ‘The Brexit Effect’ (with E. Bressanelli and E. Massetti, Routledge 2023). On Brexit, he has also co-edited a recent Special Issue for the International Political Science Review (2022). His work has also appeared in journals like Government & Opposition, West European Politics, British Journal of Politics and IR, South European Society and Politics, Parliamentary Affairs, and others. In 2023, he will act as Co-chair of the Section on ‘Illiberalism and Populism’ at the ECPR General Conference in Prague.

Filippo Tronconi is professor of Political Science at the University of Bologna. Between 2019 and 2022, he has proudly co-edited (with Martin Bull) the Italian Political Science Review, the flagship journal of the Italian political science community. His field of study is comparative politics. Most of his research has focused on territorial politics, political parties, elections, and political elites. Among his publications: Beppe Grillo’s Five Star Movement: Organization, Communication and Ideology (Routledge) and Politica in Italia, edizione 2018 (Il Mulino). He is currently working on a monograph on Brothers of Italy, together with Gianfranco Baldini and Davide Angelucci.

One thought on “Brothers and Sisters of Italy: From Fascist Roots to Normalization — A Double Interview”